In this edition, GCIR President Marissa Tirona speaks with Katherine Perez, Director of the Coelho Center for Disability Law, Policy, and Innovation at Loyola Law School. Read on as Katherine shares her thoughts about building power for immigrants with disabilities, working at the intersection of movements, and how philanthropy can support and strengthen the work of immigrants with disabilities.

Please tell us about yourself and your organization.

I am a third-generation Mexican American Latinx queer disabled woman and the first in my immediate family to graduate from college. I developed a deep sense of disability justice at a young age because my younger sister is autistic and went through special education and confronted a lot of discrimination.

I personally grew up with psychiatric disabilities, including obsessive compulsive disorder, PTSD, depression, and anxiety. However, I didn’t identify as disabled until I got to law school and started to learn about the disability rights movement and disability law. That is where I met other people with psychiatric disabilities who identified as disabled and realized I was part of the disability community.

After a fellowship with the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, I developed a passion for the law. With the goal of combining this passion with my commitment to disability justice, I went to law school to become a disability rights attorney. But when I got there, no one was talking about disability justice at all—there wasn’t a single class on the topic. I wanted to do for disability issues what Kimberly Crenshaw did for critical race theory and draw attention to the intersection of race, disability, and the law. That desire led me to pursue a PhD in disability studies so that I could fuse it with law and policy.

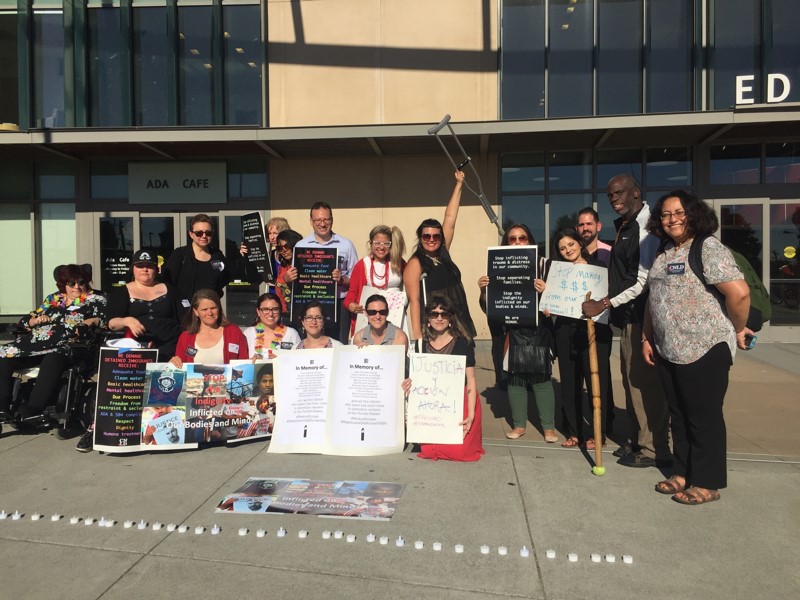

While pursuing my PhD in Chicago, I observed that the disability rights movement is very white, not at all intersectional. In 2015, I co-founded the National Coalition of Latinxs with Disabilities, or La Coalición Nacional para Latinx con Descapacidades (CNLD), an intersectional advocacy organization that addressed issues of Latinidad and disability, including transportation, health care, and others. At the time, Trump was using immigrants as scapegoats during his presidential campaign. We at CNLD felt the urgent need to work on immigration, and that’s how I came to the immigration space.

I am now Director of The Coelho Center for Disability Law, Policy and Innovation at Loyola Law School, where we center disabled people of color in our work. Even though my area of expertise is disability rights law, I have come to see the urgency for work at the intersection with immigration and have worked furiously to learn about immigration law in the past few years. Now I know enough about immigration law and policy to critique it and stir up some good trouble, bringing people together to think critically about these issues.

When you have seen power building work successfully, what were the conditions that made that possible?

For CNLD, it was about bringing the stories of our community that often go untold to the larger conversation and making sure those who were often excluded were at the table. For example, we joined the Protecting Immigrant Families coalition to make sure that stories of disabled immigrants were told and that their needs were considered in efforts to fight the Trump administration’s punitive public charge rule changes. And when DACA was being attacked, I went out and interviewed DACAmented and disabled folks, and we told their stories with their permission. We had no money, but we had power. We had grassroots power—the power of the people.

Working at the intersection of disability justice and immigration issues, what challenges or opportunities have you experienced, including in your interactions with funders?

Exclusion of voices and the siloing of issues is a major challenge. There’s a divide between immigrant justice groups, disability groups, queer groups, and other affinity groups. We’re all so focused on our own issues, but we need to come together so we can listen to each other and work together. To help meet this need, we are planning an immigration and disability conference so we can shape what we think the policy outcome should be based on a mutual understanding and definition of the problem.

For funders, a way to help address this problem—the schism between movements—is by supporting conferences like these to create intersectional spaces.

What are some effective funding strategies you’ve seen to support this work?

I worked with Ford Foundation while at CNLD. They didn’t have a disability portfolio but were starting to dip their toes in. They reached out to CNLD and Access Living, and we came up with a proposal to hold a conference in Chicago, bringing together a coalition of Illinois immigration and disability folks to work together on this intersectional issue. Our proposal also focused on research because the existing research is not really disability justice-focused; it’s more medical model-focused and emphasizes the health perspective. There’s a dearth of knowledge and of stories being told about disability justice in the academic space. Numbers from the census alone don’t fully capture the nature and the needs of our community. We need both qualitative and quantitative information.

What are some of the most consequential policy changes you are working toward to advance immigration and disability justice? What could elected officials do to advance these priorities?

The public charge rule is demonstrative of how our system is rooted in and inextricably linked with ableism. (The Immigration Act of 1882 denied entry to “any convict, lunatic, idiot, or any person unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.”) That this 1882 law is still on the books is problematic. Protecting Immigrant Families is trying to narrow the scope of the rule so that fewer people are deterred from accessing vital public services for which they are eligible out of fear of potential immigration consequences. But in the process, disability justice gets reduced to one line. I think our long-term goal should be to get rid of the law altogether. The narrative of the meritorious immigrant is inherently ableist and racist. We should be working on reimagining the whole foundational elements of this system.Healthcare policy is another huge issue. I teach the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) every year to my law students. It’s the law we have, and I go back and forth between thinking that it’s a good policy and that it’s an inadequate policy.

Ultimately, I feel like it’s a strong law that is worth upholding and investing in. So, another policy goal needs to be strengthening the ADA and funding its implementation. It is civil rights legislation that exists on paper, but there is no funding for entities to build accessibility into their systems.

The case CVS Pharmacy Inc. v. John Doe One that was poised to go before the Supreme Court is a powerful example of the importance of the disability law and policy community in combating healthcare injustices. CVS was sued by HIV patients claiming that the way they were required to receive their medication—by mail or at a CVS store rather than at a neighborhood pharmacy—amounted to disability discrimination. It was non-intentional discrimination, but the problem is that much disability discrimination is non-intentional and is based on negative attitudes. Ultimately, CVS dropped its Supreme Court challenge and committed to pursuing policy solutions in collaboration with the disability community. This case had a profound impact on the disability rights movement.

We are currently fighting yet another court battle to save the ADA in Payan v. Los Angeles Community College District, in which the Supreme Court could decide that federal law prohibits only intentional forms of disability discrimination, thereby undoing 40 years of hard-won civil rights for people with disabilities.

What is your vision for the next five to seven years?

I’m focused on training the next generation, promoting new disability justice leaders with lived experience, and creating a leadership pipeline in our communities. To do this, I created a disability fellowship at The Coehlo Center. The fellows—25 of them this year—are already leaders even though they are only in their teens and early 20s. The reality is that power is concentrated behind closed doors, so the goal is to put our people behind those closed doors and put them in leadership positions. We’re motivating folks, sharing power, building capacity, opening doors, and creating connections for those who may not otherwise have them. I’m very proud of that program. But it always comes back to funding. As director of a nonprofit, I appreciate more than ever the importance of that funding. There’s a lot more work to do, and we need more funding to get it done.